MEDICAL SPRINGS, Ore. — In 2008, gray wolves returned to Oregon — more than 60 years after the last one was shot and killed for a bounty. The predators weren't shipped in, but allowed to wander over from neighboring Idaho, protected under the Endangered Species Act.

Just three years later, the federal government determined that enough gray wolves had returned to eastern Oregon that they could be removed from ESA protections there. And in 2015, Oregon took wolves off the state endangered species list as well, though there are still restrictions on killing the animals under the state's wolf plan.

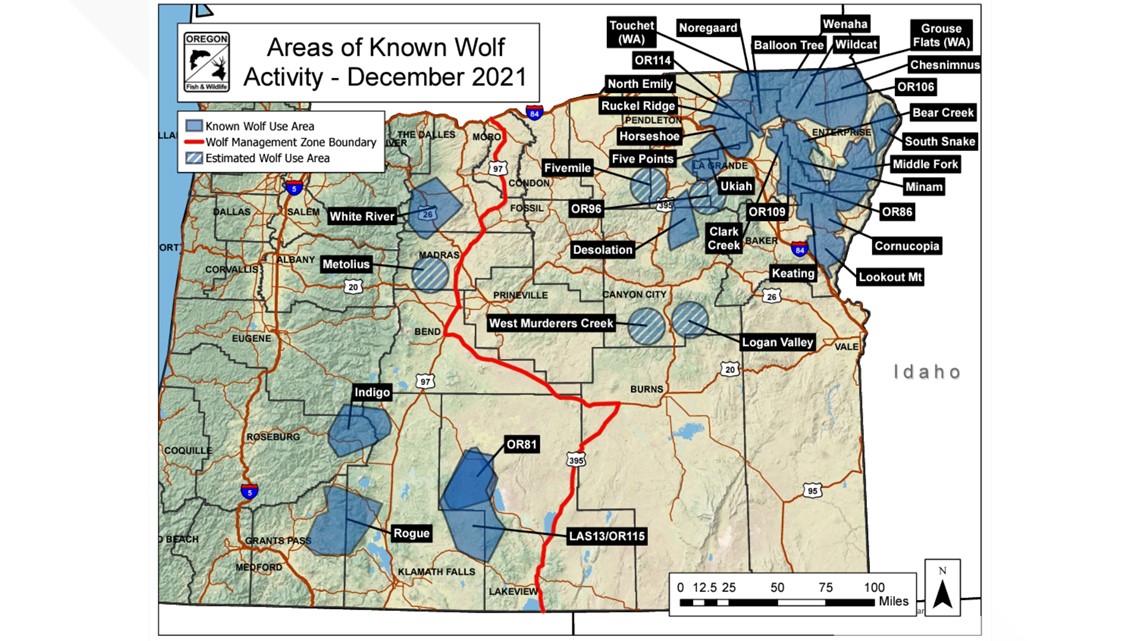

By the end of 2021, the state reported at least 21 wolf packs in Oregon, with evidence of at least 175 wolves.

A map from the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife shows where those wolf packs are known to frequent. For the vast majority, their territory is in the northeastern corner of the state.

So, during a recent trip out to eastern Oregon, The Story's Pat Dooris and a camera crew headed out that way — 100 miles north and east from John Day, in the middle of a snow storm — to reach a tiny town called Medical Springs on the edge of Union County. The area is home to thousands of cattle, as well as the far-flung ranchers who raise them.

The primary purpose of The Story's trip out east was to find out more about why rural Oregonians are frustrated, some of them enough to support the state secessionist "Greater Idaho" movement. Much of that anger stems from a feeling that western Oregon's urban areas dictate policy for the rural east — and wolves are a part of that story.

"I'm not a biologist here, but it seems to me like there's three packs around this area, and it's breeding season right now," said Coleman Lay. "So you tell me what the wolf numbers are gonna look like here in another few months when those females have pups."

Lay is a 30-year-old rancher out here in the Medical Springs area.

"So, I am the sixth generation, and my son is the seventh. My great-great-great-grandfather homesteaded up the road about seven, eight miles, about 125 years ago and built a family here, and I'm the tail end of him I guess," Lay said. "My little boy and little girl are the seventh."

Lay has a degree in marketing and supply chain management from Boise State. He loves this land and his herds of cattle.

Right now, it's calving season. Lay has a thousand "mama cows," as he called them. The moms of two little ones didn't survive. Lay showed Pat Dooris how to give one of the calves a bottle of warm milk.

At the end of the feeding, Dooris learned that it's best to keep one's guard up around hungry calves — he earned a shot to the groin for his efforts. It's a good lesson for a reporter from the city.

Wolves at the door

When talking about the Greater Idaho movement, Lay echoed a lot of what other eastern Oregonians have told The Story.

"The Greater Idaho movement to me is more of the fact there's just so many people who are so tired of like, not having a say. They're like, 'Hey, my life is basically being dictated by a completely other side of the state that has nothing … really has no clue what we're dealing with over here.'"

During the birthing season, Lay spends long days checking on the young calves. But he's got one main concern that looms over everything else — wolves.

Wolves aren't a theoretical problem out here. In early February, wolves came to Lay's ranch and attacked and killed his dog, Dodge.

When wolf predations like this happen, it's supposed to be reported to the state. Biologists from ODFW then come out and investigate to confirm that it was indeed a wolf attack.

The state confirmed to Lay that Dodge had been killed by wolves. Lay said that it happened overnight, while he slept with a white noise machine on.

It's not the first time that wolves have attacked here. Lay shared a picture of a cow that had been killed by wolves, and he said there are others.

In late February, ODFW approved the killing of two wolves near Medical Springs after three attacks in pasture lands. Three more wolves have been legally killed in eastern Oregon this year for attacking livestock. When the state does allow for killing of wolves, it's the state that does it — ranchers are generally supposed to keep their defenses non-lethal.

"This is a major problem," Lay said. "I don't feel safe going on walks with my dogs, I don't feel like my family … like I gotta have an eye on 'em at all times."

For years, gray wolf populations in Oregon have shown steady growth, signs that they are taking root again after being wiped out in the 20th century. But 2021, the last full year of ODFW data, could be best described as a bloodbath for everyone involved.

Throughout the year, 21 of Oregon's gray wolves died — indiscriminately poisoned by poachers, hit by cars or shot by wildlife officials because of chronic predation. The number of deaths meant that the wolf population remained almost flat year-over-year.

At the same time, wolf attacks on livestock were up in 2021, totaling 49 confirmed incidents versus 31 in 2020, according to the ODFW's reports.

Beyond compensation

Lay shared the news of his dog's death on Facebook. He said that people might write off the death of a cow or other livestock, but he wanted the world to know that it can happen to beloved pets as well.

"I wanted to post that to realize like, 'Hey, this is what we're dealing with. Like, we're really struggling' ... There might be some folks that hear or see of a dead cow picture ... they're like, 'Well, so what? I don't have cows. Cows are cows,'" he said. "That's kind of what happens out west, you know, like that's the wolf — cowboys deal with wolves all the time. That's just what happens. But then when you add a picture of a dead dog on your, on your page or whatever, they're like, 'Wow.' That resonates with a lot more people."

Regardless, Lay said, some people don't seem to understand that wolves are a real threat out here.

"There's some people that, you know, almost think that a wolf has more right to live than you or I," he said. "There's some of the nasty comments you'll get and, you know, I get some of these people are just sitting behind a computer acting tough or whatever, they're gonna come, you know, kill your family or whatever, if you ever harm a wolf."

The Oregon legislature set up a wolf kill compensation fund in 2011. It's a mixture of state and federal tax money that pays for non-lethal prevention measures to protect livestock from wolves. It also pays for animals that are hurt or go missing in a confirmed wolf attack.

In 2022, the fund paid out $393,682 for both wolf attacks and prevention measures. Payouts since the fund began total $1,187,000.

But the fund isn't much comfort for ranchers like Coleman Lay, who wish Oregon's leaders on the west side of the state knew what it was like to live with wolves on the east side.

Soon, Lay will take his cattle up into the hills to graze on the edge of the stunning Eagle Cap Wilderness — where they'll be in the middle of wolf country.

"There's just so many wolves in one specific area. And I don't — people probably already know I don't like wolves, but I also see my opinion's not the only one that matters," Lay said. "So what I am asking or saying is too much of anything is not good. If we have way too many wolves in one area, there needs to be ways or avenues (that) ranchers or outdoorsmen or sportsmen alike can finally have to limiting numbers."

This story is part five of a series of stories on eastern Oregon. Catch all of the previous segments below or look for updates on The Story's page.

- PART ONE: Eastern Oregonians say they've been ignored by state leaders for too long

- PART TWO: What's the appeal of 'Greater Idaho' for eastern Oregonians?

- PART THREE: Idaho isn't such a great idea for some disgruntled eastern Oregonians

- PART FOUR: 'We still have hope': Eastern Oregon sheriff isn't ready to endorse 'Greater Idaho' movement

- PART FIVE: Union County rancher describes the cost of living in Oregon's wolf country