BOISE, Idaho — This article originally appeared in the Idaho Press.

Greg Hampikian, director of the Idaho Innocence Project, sat in a cramped, cluttered office in Boise State’s University’s science building on Friday. His long white hair flowing, he ate his salad with chopsticks while employees worked in the lab.

He’s a busy guy, even though for the third time in its history, the Innocence Project has suspended legal services because of funding. The project’s goal is to “correct and prevent wrongful convictions in Idaho through case investigation, litigation, research and education.”

The project’s lawyer left in March and there aren’t enough funds for a new full-year contract for Idaho cases. Hampikian is hoping he can work with an outside entity to take on the legal void left behind.

In the meantime, Hampikian said the lab is working only on DNA aspects of cases through the Forensic Justice Project. The innocence project is part of the Forensic Justice Project.

“I’ve had to contact our clients and tell them your legal parts are on hold,” Hampikian said. “And those are difficult conversations.”

Professor Greg Hampikian discusses his work as director of the Idaho Innocence Project during an interview in his office at Boise State University, Friday, April 19, 2024.

The project, which began in the mid-2000s, notably helped free Sarah Pearce and Christopher Tapp. Tapp was convicted in 1998 for the rape and murder of Angie Dodge in Idaho Falls. He was released from prison in 2017, had his conviction vacated in 2019 and in 2022, Idaho Falls agreed to pay him $11.7 million. Tapp died in Las Vegas last year. The death was ruled a homicide.

Pearce was released in March 2014 after serving over a decade for a crime she said she didn’t commit. She was charged with aiding attempted murder and sent to prison in 2000, but a judge later re-sentenced her to five years probation.

The judge’s decision was prompted by concerns over discrepancies in witness testimony and issues with evidence.

Hampikian himself was involved in freeing Amanda Knox, the American college student accused of murder in Italy in 2007.

Hampikian earned his doctorate in genetics at the University of Connecticut. His work has been inspired by his mother’s sense of justice and his father’s love of science.

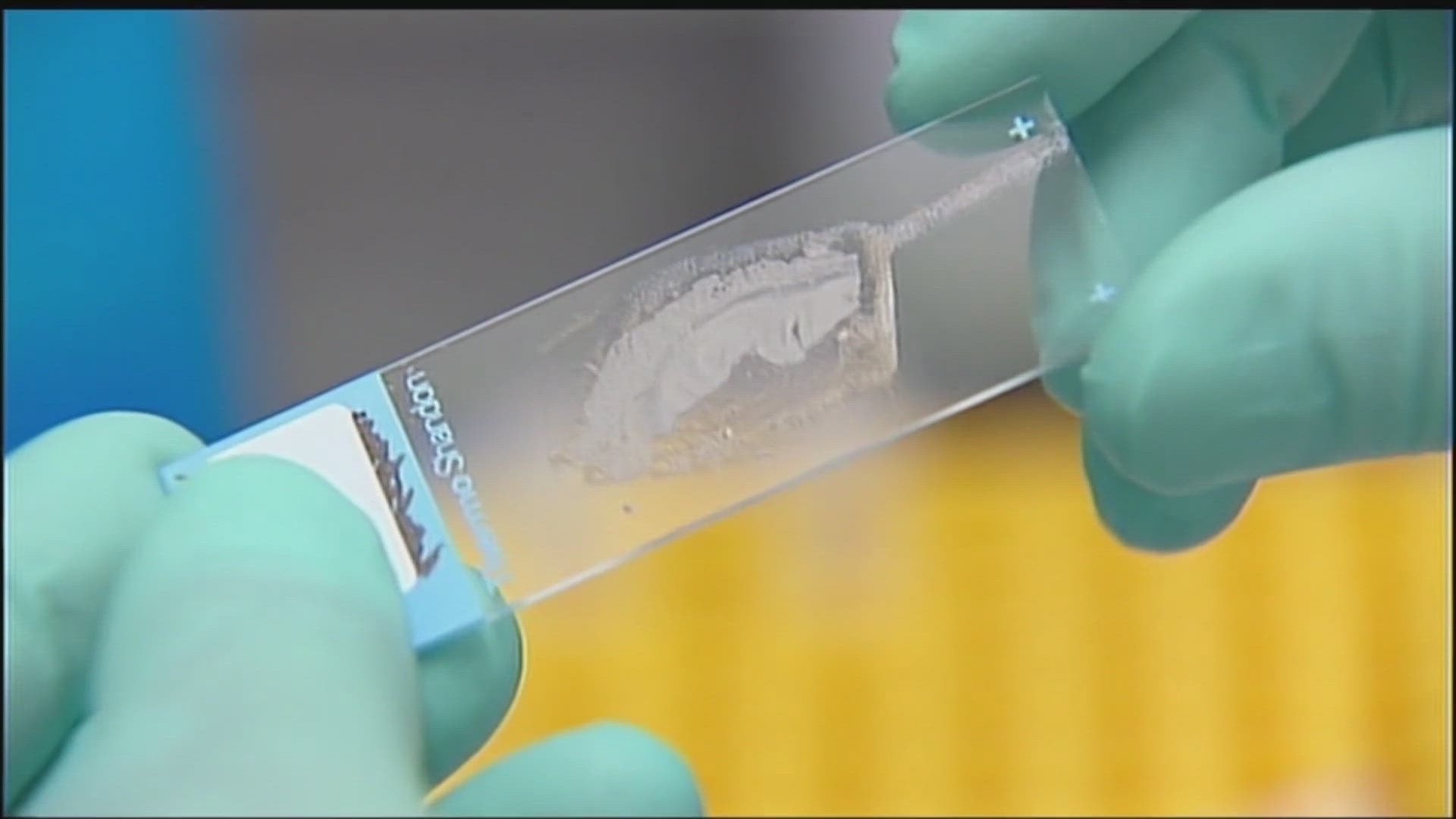

Lab equipment is ready for use in the DNA lab of Greg Hampikian at Boise State University, Friday, April 19, 2024.

He kept in touch with people from school who had gone to work with DNA, an emerging field at the time. He taught in Georgia, where he asked Calvin Johnson, who had gone to prison for 16 years for a rape he didn’t commit, to speak to his class. DNA evidence ultimately exonerated Johnson.

The book Johnson and Hampikian wrote together is sitting on Hampikian’s bookshelf. Its title: Exit to Freedom. Johnson worked through his anger in prison over years, but he “became joyful even in the hellish circumstances.”

“He taught me so much about hope, forgiveness,” Hampikian said.

The Idaho Innocence Project began as a student organization at the University of Idaho, but Hampikian worked to bring it to Boise. He started officially working with the project in 2006.

Hampikian has seen plenty of issues in the court system over the years, like labs not taking photos of sperm cells in their microscopes or referring to evidence in front of the jury in misleading terms. He took issue with the phrase “The absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence,” — essentially, the idea that just because there are no DNA traces of someone at a crime scene, that doesn’t mean they weren’t there.

But he doesn’t believe the people within the system are doing anything wrong. And Hampikian still has optimism for the court system.

Professor Greg Hampikian pulls down a book he wrote with Calvin Johnson, who had gone to prison for 16 years for a crime he didn’t commit, in his office at Boise State University, Friday, April 19, 2024.

“The vast majority of people in the whole system are trying to do the right thing. The problem is the structure,” Hampikian said. “Maybe our system could be trying something different.”

Studies suggest that roughly five percent of people in U.S. prisons are innocent, said Diane Raptosh, an english and criminal justice professor at the College of Idaho.

“There should be zero,” Raptosh said. “The number should be zero.”

Wrongful convictions can happen for many reasons, including mistaken eyewitness identifications, false confessions, misconduct by police or prosecutors or unreliable forensic evidence. False convictions tend to disproportionately affect Black people, according to the Innocence Project.

Sometimes people who are wrongfully convicted have to wait for many years, Raptosh said.

“People think that whoever goes to prison must be a total monster, but it’s really not true,” Raptosh said.

This article originally appeared in the Idaho Press, read more on IdahoPress.com.

Watch more Local News:

See the latest news from around the Treasure Valley and the Gem State in our YouTube playlist:

HERE ARE MORE WAYS TO GET NEWS FROM KTVB:

Download the KTVB News Mobile App

Apple iOS: Click here to download

Google Play: Click here to download

Watch news reports for FREE on YouTube: KTVB YouTube channel

Stream Live for FREE on ROKU: Add the channel from the ROKU store or by searching 'KTVB'.

Stream Live for FREE on FIRE TV: Search ‘KTVB’ and click ‘Get’ to download.