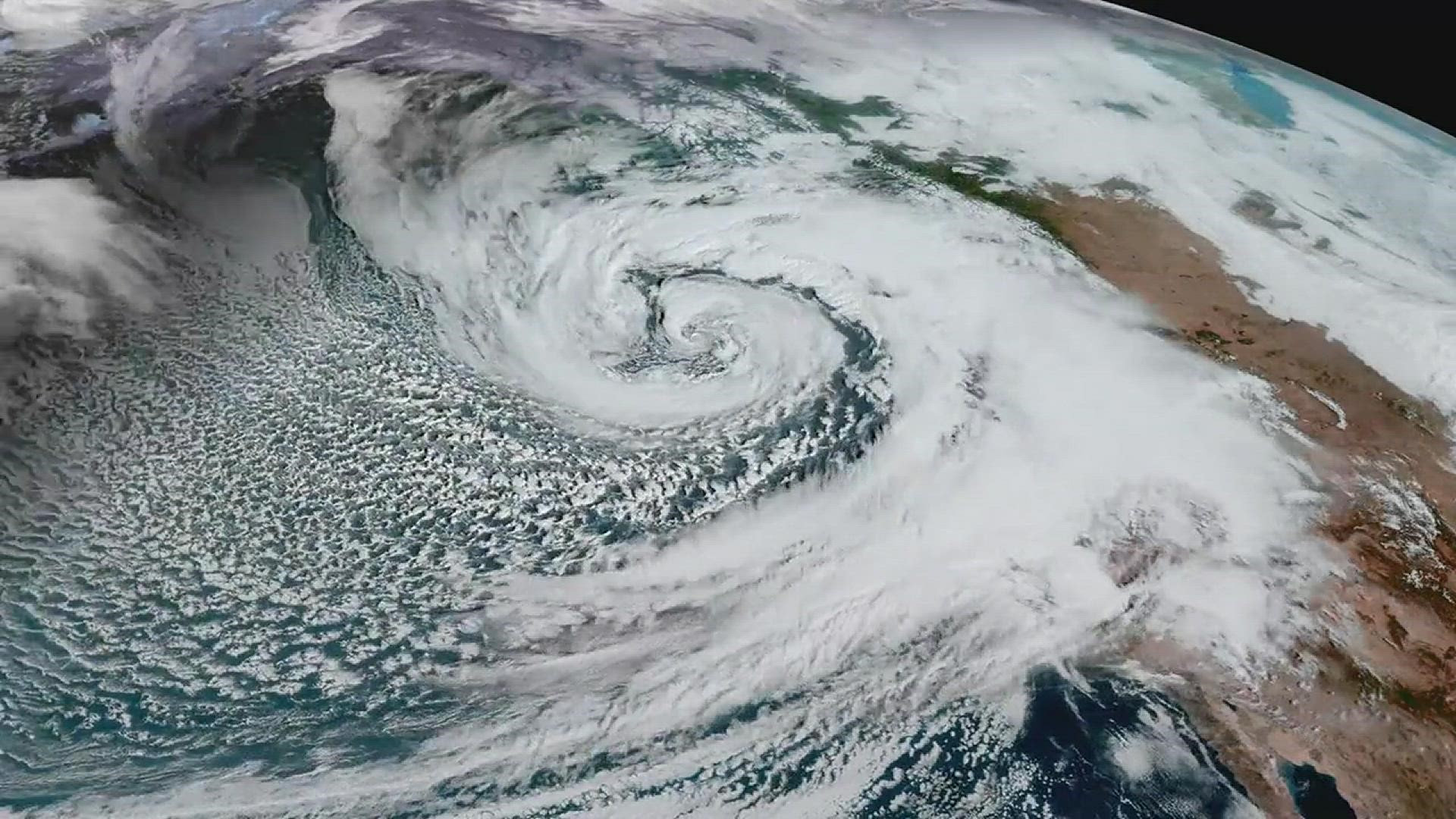

PORTLAND, Ore. — Even now, several days after the bomb cyclone exploded off the Oregon and coast and fizzled it's way into Canada, people are asking me about it. Here's a break down of where the phrase came from and an answer to the question that always comes up about strong windstorms on the West Coast: why are they not called hurricanes?

Where did 'bomb cyclone' come from?

The phrase "bomb cyclone" was coined by a graduate student and his professor at MIT, who were researching storms of the Pacific and Atlantic that developed really quickly and really strongly. They described such storms as having “explosive” development, and from there was a short step to calling them bomb cyclones.

The process that creates these storms is one of my favorite terms in meteorology: BOMBO-genesis.

And if you're confused or hung up on the word “cyclone”, let me clear that up. Cyclone is the technical word for a storm. Hurricanes are tropical cyclones, our typical fall or winter storms are called mid-latitude cyclones. An area of high pressure is technically an anti-cyclone. They occur in the northern and southern hemisphere. Some places like Australia call their hurricanes tropical cyclones, or just cyclones. Which they are. But the word cyclone has a broader meaning than that in meteorology, and can accurately be used to describe storms in any part of the world.

Tornadoes are not cyclones. They’re tornadoes. In some parts of the country tornadoes have been called cyclones, but I think that misnomer is fading away.

Back to the bomb cyclone. Frederick Sanders, the MIT professor who coined the term, knew these storms were dangerous to coastal communities that sometimes let their guard down after hurricane season. Bomb cyclones can do just as much damage and be just as dangerous, so if the alarming name helped draw attention and raise awareness to the dangers of rapidly and intensely developing fall and winter storms, Sanders felt that was a good thing.

Why aren’t bomb cyclones called hurricanes?

The answer is because while still a strong storm like a hurricane, it’s a completely different animal. Like grizzly bears and polar bears. They are both immensely huge and powerful animals that can eat you and while both are bears, they are different animals.

Hurricanes and bomb cyclones are both strong storms, but they develop differently and are structured differently, so they are not the same thing.

Hurricanes derive their strength from very warm, (greater than 80-degree) ocean water. The warm water evaporates from the ocean, but when that water vapor condenses to make cloud, it releases a tremendous amount of latent heat. That heat energy is the source of a hurricane’s power. The strongest winds in a hurricane are in the lower part of the atmosphere. Winds high above a hurricane are very weak.

Not the case with bomb cyclones. Bomb cyclones derive their energy from the jet stream, and while they often form where ocean temperatures are changing the most, this isn’t necessary for the storms' growth or maintenance.

How this recent bomb cyclone compared to others

The Oct. 24, 2021 bomb cyclone set a record for lowest pressure ever recorded in the Northeast Pacific Ocean at 942 millibars (mb). For the entire Pacific Ocean, that record goes to a storm in the Aleutian Islands on New Years Eve, 2020. That bomb dropped to 921 millibars. As a reference, Hurricane Sandy dropped to 938 millibars, Hurricane Wilma holds the record for the lowest sea level pressure recorded on the planet at 882 millibars.

I’m geeking out on the numbers here, so broader context maybe required. Average barometric pressure is 1013.2 millibars. When pressure starts to climb around 1030 mb range, that’s considered high pressure. I’ve seen it as high as 1065 mb in Northern Canada, and the world record was set in 1968 in Siberia at 1084 mb.

When the pressure drops below 990 mb, that’s considered low. You can see that the bombs in the 920-940 range are really low, and this matters because generally, the lower the pressure of a storm, the stronger the winds.

To be classifies as a bomb cyclone, the pressure has to drop at least 24 mb in 24 hours. The October 24 storm dropped an impressive 46 mb in 24 hours.

What about the impacts?

There were 85 mph winds gusts on the Long Beach Peninsula of Washington. The storm generated 40 foot seas. A container ship listed so severely it lost its containers. They were last seen drifting north off Vancouver Island.

San Francisco had its wettest October day ever with 4.02 inches of rain. Sacramento had its wettest day ever with 5.44 inches of rain. That, following a stretch of 212 days with zero measurable rain that ended on October 18.

The future of bomb cyclones in a changing climate

Research in California suggests these drought to deluge scenarios may become more common in the years ahead. Bomb cyclones themselves may also become more common at higher altitudes, but less common down here below 45-degrees latitude. The line runs through Salem, Oregon and intersects the east coast near Halifax, Nova Scotia. This jives with the premise that the jet stream will be receding northward under a warmer climate.

Based on my professional recollection and not research, we typically see about two to four bomb cyclones a year off the West Coast. Some never get any closer to the Northwest than the Aleutian Islands. Luckily for us, most explode far enough offshore that the West Coast is spared the greatest impacts of the storm, like the one we just had.

On the plus side, there was the hugely beneficial rains. Shasta Lake in Northern California, the state's biggest lake, rose three feet and Lake Oroville, a couple hours south of Shasta, rose 10 feet.

It’ll take many more storms to end the drought in California, but our recent bomb cyclone may have just blown up the log jam of drought. We’ll need a good wet winter with lots of valley rain and mountain snow to raise the reservoirs back to normal, detonate the drought and designate it to history.

Matt Zaffino is also the host of KGW's podcast Under the Big Umbrella. It explores some of the quirky, interesting, mostly weather-related topics that will leave you feeling wow’ed and smarter.