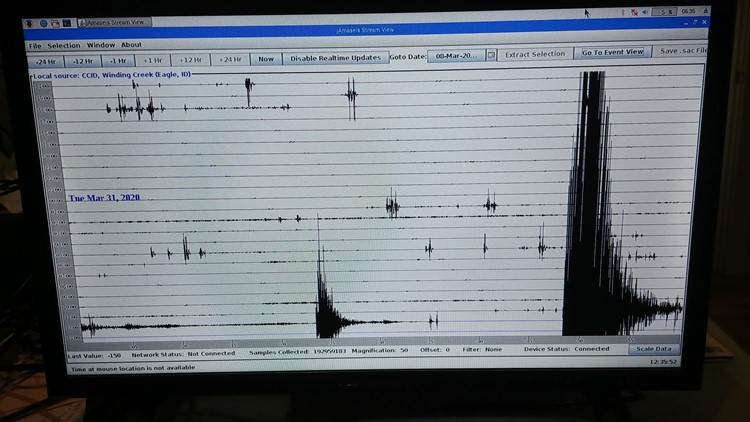

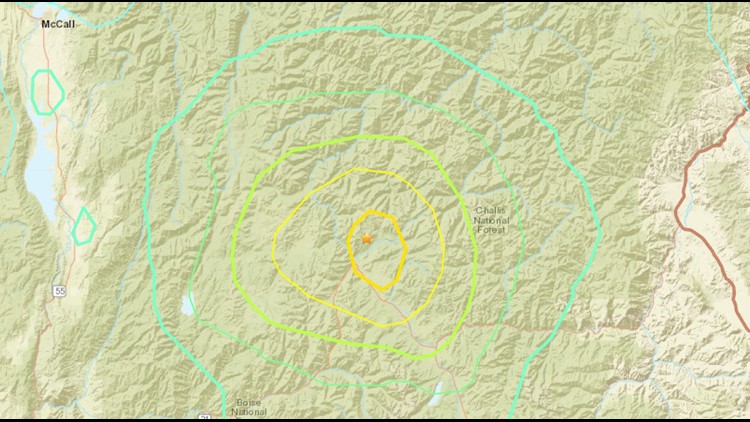

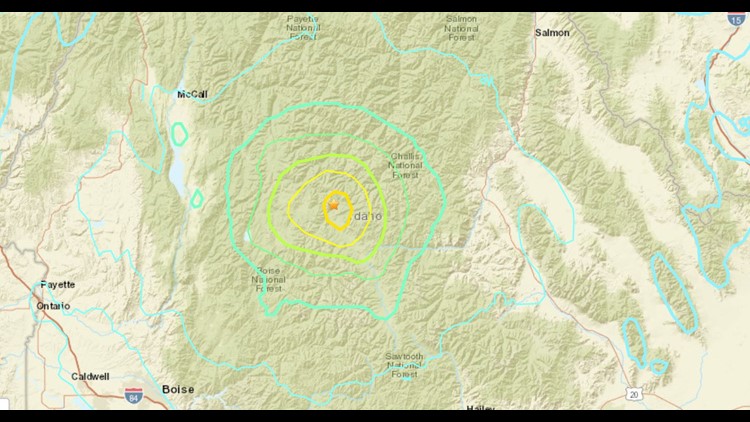

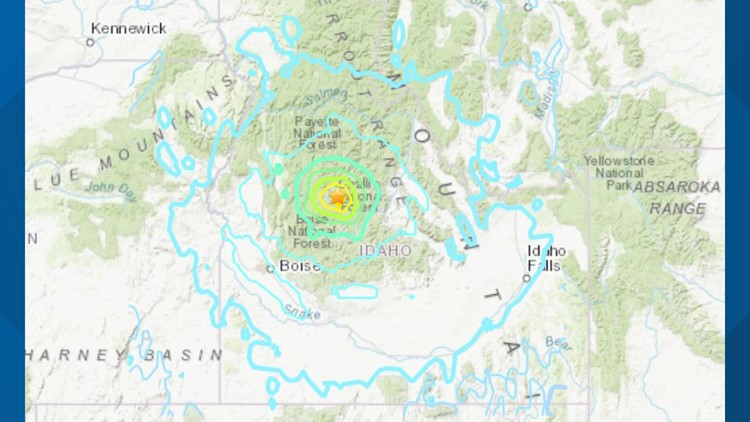

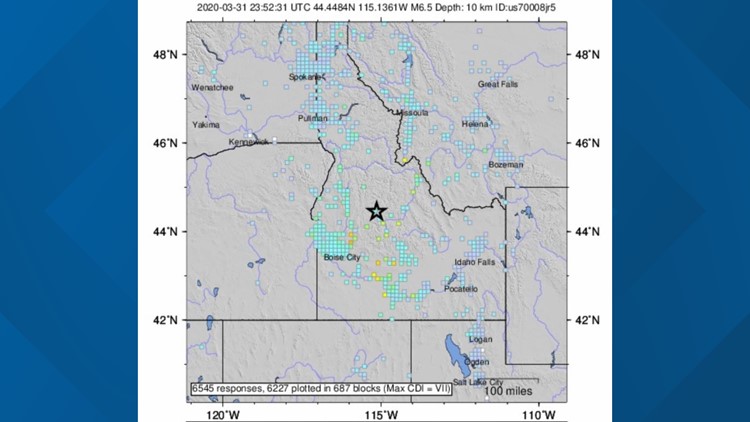

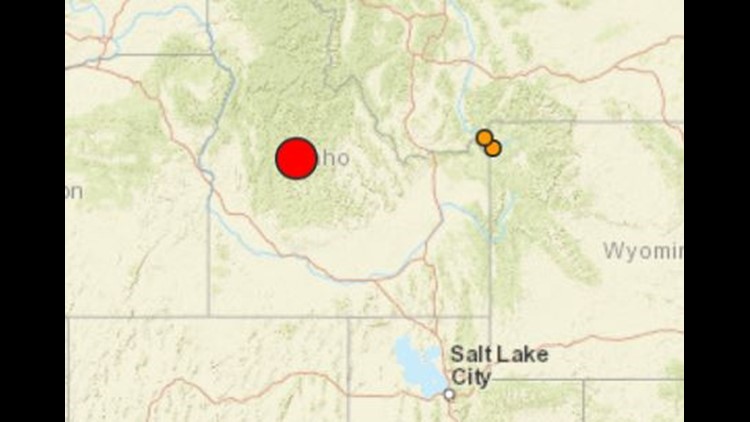

BOISE, Idaho — Researchers at Boise State University have won two grants to study the aftershocks of the magnitude 6.5 earthquake that happened March 31 in the Sawtooth Mountains northwest of Stanley.

The National Science Foundation and the U.S. Geological Survey awarded the grants to a team of Boise State geoscience researchers who are working to place seismometers and infrasound sensors in the field to collect real-time data on aftershocks from the March 31 quake.

The two grants for the Boise State researchers add up to $122,000.

The main goal: just learn more about the aftershocks and their possible effects down the road.

"What we will be doing the next nine months, and hopefully a little longer if we can stretch the budget, is to continue monitoring the equipment that we've set up, downloading data regularly, moving equipment if we need to, and installing new equipment if we have the opportunity," said Dylan Mikesell, an associate professor of geosciences at Boise State. "Right now we've got around 50 sensors in the area. The goal now with this grant is to keep those sensors out there and keep them working so we can record as many aftershocks as possible."

Since the March 31 earthquake in the Challis National Forest, there have been more than 900 aftershocks with a magnitude higher than 1.5.

"We're at about 20 to 30 (per day) on a strong day, ten on a weak day," Mikesell said.

Mikesell and the research team hope to pinpoint the locations of the aftershocks so they can map the active faults in Central Idaho, and identify if any stress from the March 31 earthquake has transferred to other faults in the area.

They've already made some interesting findings.

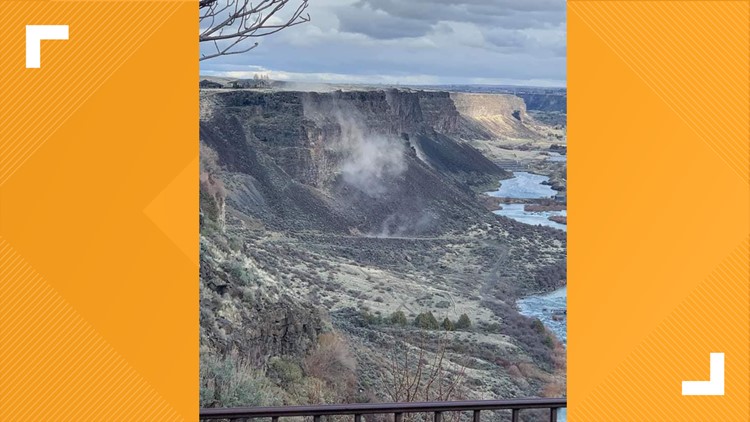

"One of the reasons the NSF gave us the go-ahead with the grant is we not only have seismologists at Boise State, we have acousticians who study infrasound in the atmosphere. and immediately after the main shock, the day after, myself and another professor went up to the epicenter and installed some seismometers and infrasound sensors, and what we noticed was some really interesting infrasound signals happening directly after a seismic wave passed through the ground, and those were seismic waves generated by the aftershocks," Mikesell said.

Acousticians use infrasound sensors to study very low-frequency pressure changes in the atmosphere, like the rumbling of earthquakes.

"We're seeing some very interesting energy transfer from the solid earth into the atmosphere, and then it sort of bounces around in the mountains," Mikesell said. "We haven't really seen this before from such a close distance to the earthquake -- we're talking about making these observations within a few miles of the quake epicenter and the aftershock epicenters."

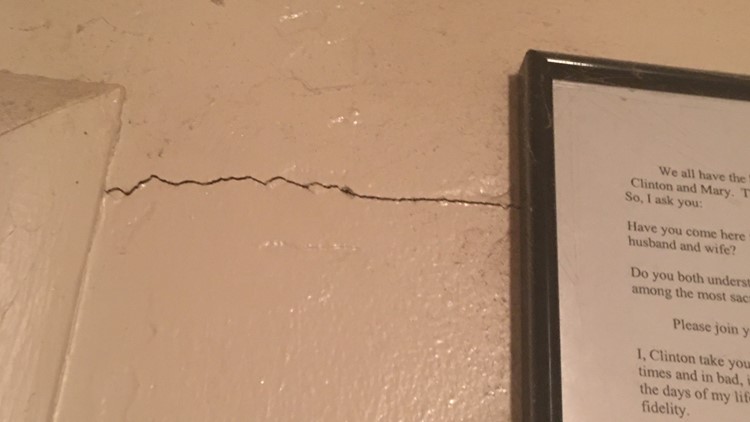

The researchers hope that data and the information collected in the future will help them figure out how the ground is going to shake in areas with taller buildings and buildings with un-reinforced masonry, both of which pose an added danger in earthquakes.

Less is known about the earthquakes in Idaho compared to those along the West Coast that often shake up California, Oregon and Washington, where more seismic research has taken place, and where more sensors are in place.

One reason: most of Idaho's earthquakes, especially the bigger ones, had epicenters in low-density areas such as wilderness, forest or rangeland.

When it comes to earthquakes, Idaho hasn't experienced the major loss of life, limb or property that happened in Haiti in 2010, for example, or, on a lesser scale, in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1989.

"That's partly because we've gotten lucky. We didn't build any big cities in areas that are prone to big earthquakes," Mikesell said.

He said based on what researchers know about Idaho earthquakes up to this point, the Treasure Valley is "fairly safe."

"There's no major active faults, at least close by. That's in contrast to Oregon, California and Washington," Mikesell said. "We know that there's a big subduction zone right off the coast, and those subduction zones can produce very, very large earthquakes and cause a lot of ground shaking."

He's referring to the Cascadia subduction zone, which stretches from the coast of British Columbia, Canada, to the Mendocino Coast in Northern California. In that zone, the Juan de Fuca plate out in the ocean is moving toward the North American plate on the continent, and eventually could be shoved beneath that plate.

The massive magnitude 9.0 earthquake that struck Japan in 2011 and triggered a deadly tsunami was a subduction zone earthquake.

Back to the ongoing research in Idaho, Mikesell said, "it's going to be really interesting in terms of understanding the energy transfer between the solid earth and the atmosphere as it pertains to earthquakes."