BELLINGHAM, Wash. — It’s the most northwestern university in the mainland U.S. and it sits right under the nose of a major mystery.

“We have these active volcanoes right in our backyards,” said Susan DeBari, PhD, Professor of Geology, Western Washington University.

Western Washington University hosts a geology program dedicated to putting together the puzzle of what makes up some of the most dangerous volcanoes in the United States.

“You look at that volcano, right?" DeBari said. "It just looks like a mountain with snow on it. But, I think when we look at it, we're envisioning what's happening, like 20 kilometers beneath the surface."

DeBari was studying pre-med as a sophomore at Cornell University in 1980 when Mount St. Helens erupted.

"It felt like it was from another planet," DeBari said. "I could never have imagined that I would be studying cascade volcanoes."

A few months later, a friend introduced her to a geology course and her interest was forever piqued. She changed her major and dedicated her career to studying volcanoes.

With active volcanoes like Mount St. Helens, the Pacific Northwest is the ideal place for geologists and volcanologists like DeBari.

“It was one of the most exciting pieces for me in being hired here 25 years ago, at Western Washington University, because we have these active volcanoes right in our backyards,” DeBari said.

DeBari works with fellow geologist Associate Professor, Kristina Walowski, on the project to decode volcanoes.

“I just like absolutely fell in love with not only going to these places but learning how they formed and why they look the way they do,” Walowski said.

The pair, along with a professor from Central Washington University are mapping out the inner workings of volcanoes.

And about an hour's drive from WWU's campus is the team's current muse, Mount Baker.

“Why is Koma Kulshan different and how is its personality different?” Walowski said.

They use Mount Baker’s native name, Koma Kulshan out of respect for the Native American tribes that call this land home.

“Volcanoes are creatures of habit," DeBari said. "So, if we know what happened in the past, then we can use that information to be prepared for the future."

Their goal is to figure out the story of Koma Kulshan, when, how, and why it last erupted.

Unveiling that mystery takes them to the field.

“You need a nice heavy hammer, rocks are pretty hard,” Walowski said.

DeBari and Walowski brought KING 5 to a rock face in the hills of Koma Kulshan.

The team discovered the rock face is the most recent massive eruption from the volcano, and it dates back 10,000 years.

“So, this is a 10-kilometer-long lava flow who ends up in Baker Lake,” DeBari said as she gestured toward the rock face.

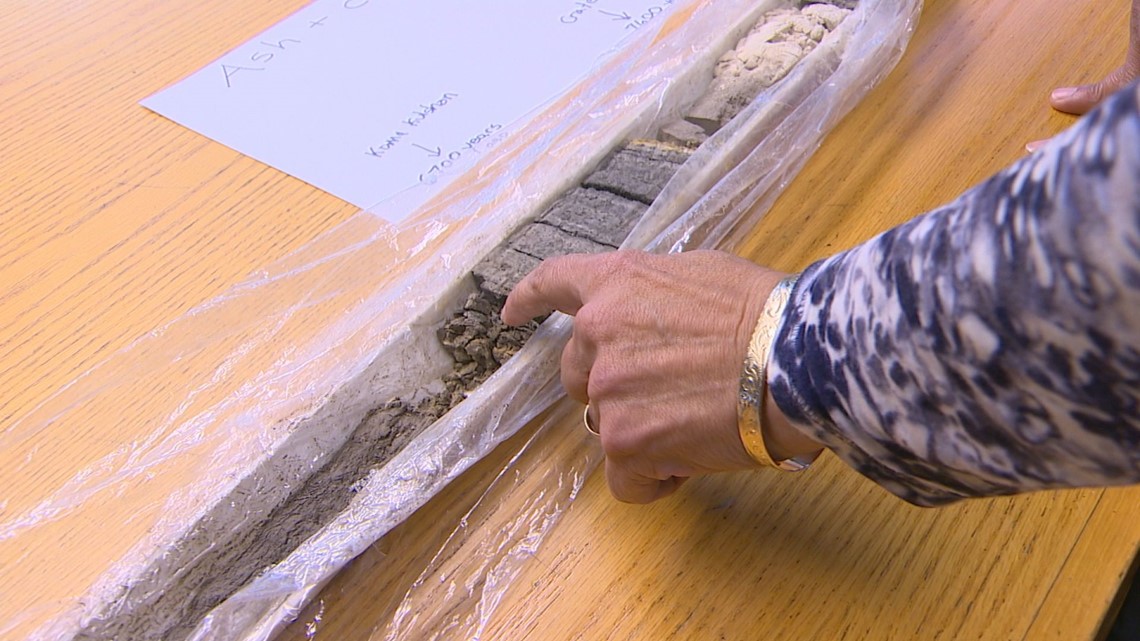

With hammers, the team breaks off pieces of rock from the volcano.

They then inspect pieces to decide if it’s a good sample to bring back to lab to study.

“These are gas bubbles that were trapped inside the lava while it was flowing,” DeBari said as she inspected a sample.

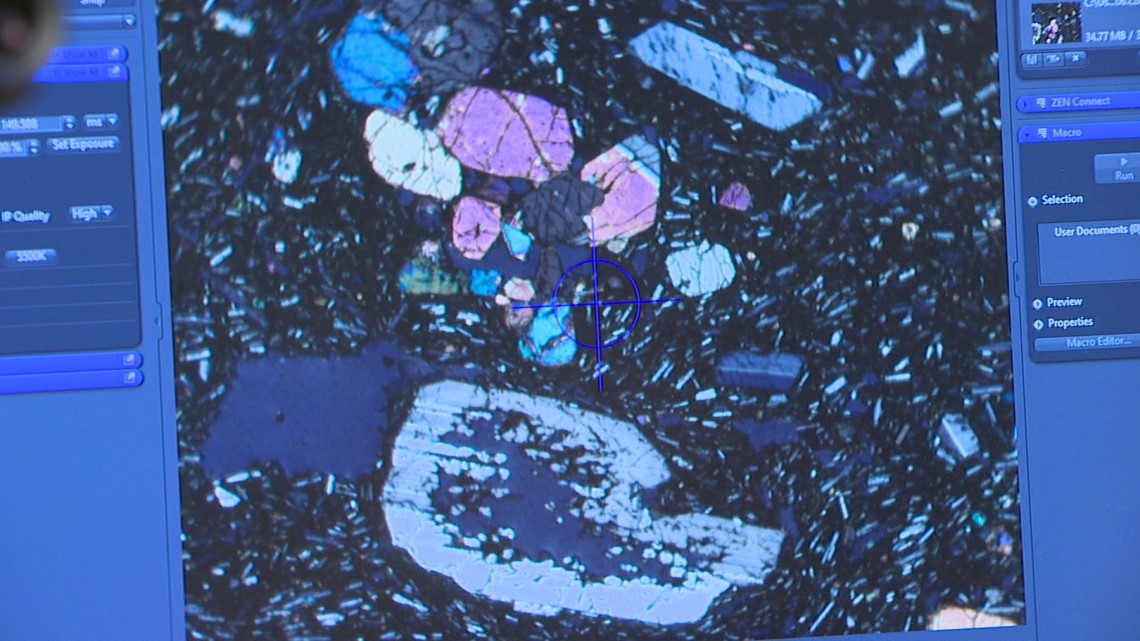

At Western Washington University’s campus, Graduate Student Amanda Florea slid a piece of the rock from Koma Kulshan under the lens of a microscope.

“We're looking at this crystal here, that's like roughly a millimeter, but then we can go over here and look at all of the teeny tiny little crystals that you can't even see with the naked eye," Florea said. "And we can look at those in a much bigger scale through this microscope.”

Florea looked at the sample through a microscope, showing the colors and reflections of the crystal.

For even an even closer look, the geologists and students used a scanning electron microscope to magnify the crystal 1000x what the naked eye can see.

It reveals rings on the crystals, similar to tree rings, showing the layers that formed it.

This gives a clue of the chemicals, temperature and pressure that formed it.

“So, this is telling the story of growth from the very core out to the edge,” DeBari said.

Understanding the environment that formed a crystal helps scientists learn the type of eruption from the volcano, whether it was explosive, has magma, or more gaseous.

Scientists use the data to build a conceptual model of what the volcano looks like beneath the surface.

They look at the volcano as a plumbing system.

The part where it erupts would be the faucet and below: a system of pipes

“Our goal is to build these conceptual models of how any individual volcano works," Walowski said. "So, what the plumbing system beneath looked like and how is that going to affect the eruption that may occur in the future?”

The conceptual models are used by the agency to plan and prepare.

“This kind of data, the Cascades Volcano Observatory, they are building hazard response plans for volcanoes that they deem are going to be the most likely to erupt next,” DeBari said. “The data that we collect is information that they use to make those sorts of decisions in the hazard response plan.”

“Volcanoes are creatures of habit. And so, if we know what happened in the past, then we can use that information to be prepared for the future."

But sometimes their studies of volcanos show them change.

The reamed most recently wrapped up the study of Augustine Volcano near Homer, Alaska.

Using their scientific methods, they determined the eruption style of Augustine volcano has changed over time.

It’s become more explosive in smaller eruptions.

The change impacts how communities around the volcano plan and prepare.

“Augustine last erupted in 2006, it also erupted in 1986, 1976 so it’s a pretty active volcano," Walowski said. "Augustine Island is really close to Homer, Alaska and Anchorage. So, a larger eruption could be really problematic, especially for air travel."

“Every rock has a story,” said Zenja Seitzinger, a Geology graduate student at Western Washington. “My project is looking at those crystals and pulling out stories of their growth that tells us about what was happening in the magma chamber in the plumbing system.”

Seitzinger hopes to take what she’s learned from the project and turn it into helping communities sitting in the shadows of volcanoes, similar to like Bellingham, home to Western Washington University, so they can plan and prepare for when an eruption happens in their own backyards.

“Having volcanoes in your backyard, it's just really cool to know that the research that we're doing is directly like impacting are important to the community that I've now come to be a part of,” Seitzinger said.

“I think that's really cool," Florea said. "Like I have the opportunity to tell the story of this volcano."

With a presence ever looming over the pacific northwest the danger that lies beneath will no longer be a mystery.